A sprite beside the pavement, a hobgoblin at the window

The steam train, and its vast expanse of iron track, have long symbolised the onslaught of rapid

industrialisation in the nineteenth century. During the early days of rail travel, a variety of superstitions

arose. Some people believed that travelling on a train could rob you of your soul because of the unnatural

speed and passengers’ separation from the earthen ground. Across the United Kingdom, rural communities

thought that railway crossings were portals where different energies intersected. At a crossing near

Wembley, during foggy conditions at night, people reported timeslips, seeing or hearing unscheduled trains

that vanished upon approach.

Several years ago, I visited the Workshops Rail Museum in Ipswich on Jagera, Yuggera and Ugarapul country.

Walking through partially dismantled Edwardian carriages and early electric engines, I began to think about

railway history in this country; and its role in collapsing distance and implementing the standardised

temporal systems that we now live by: schedules, timetables and clock time. Many of the trains and their

accoutrements, silverware in the dining cars and formal staff uniforms, are quaint and charming. It feels

like stepping into a Poirot novel. However, like a detective novel, there is something insidious behind these

picturesque elements. The development of the railway system can be linked to the consolidation of the

mechanisms of imperialism, environmental destruction, settler expansion and colonial power in this country.

The behemoth rail network stretches outwards: a serpentine infrastructure that holds conflicting stories of

mobility, connectivity and modernisation. Unwieldy landscapes and treacherous ground can be dominated

by a series of bridges, passageways, gates and intersections.

Artist Col Mac’s exhibition passing place, at the Northern Rivers Community Gallery, similarly considers such

temporal, architectural and spatial structures; exploring the metaphorical role of fences, walls, windows

and mirrors against the backdrop of local histories. Mac accumulates imagery of the pastoral landscape,

the sugarcane plantation and the idyllic suburban neighbourhood to present a series of narrative moments

which are both mystical and playful.

The phrase ‘passing place’ suggests infinite perambulation, a place or opening through which all matter might

flow continuously. At one end of the exhibition sits the sculpture, can’t get over it, a black wooden ladder that

taunts onlookers; it is impossible to ascend. The ladder seems to melt into a slippery concertina of curved

wooden folds, like the coils of a snake. The game Snakes and Ladders originated in ancient India to teach

players about karma and the spiritual trajectory of life. It was then adopted by the British Empire as a game

of chance. Now it might be seen as a metaphor for the complex ways human memory navigates time: one

might tread forwards and upwards confidently into the future only to be hurled backwards into the past

when one least expects it.

The township of Ballina, where the gallery is located, lies close to the border that separates the states of

Queensland and New South Wales, the ancestral lands of the Bundjalung people. Many elements of passing

place originate from loose references to Ballina, the area in which Mac’s grandmother was born in the 1940s

in a tent at a travellers’ campsite. Mac’s grandmother was of Romanichal heritage: the Romanichal people,

sometimes referred to as Roma, first migrated to Australia from 1788 onwards, with large concentrations

in both New South Wales and Queensland. Migration increased following the outbreak of World War Two.

Known for their peripatetic lifestyle, historically, in this country and others, Romani practices have often been

opposed by governing bodies. Colonised Australia has long been a place in which land has been a cherished

commodity, a place where land can be owned, extracted and profited from. The notion of ‘the right to roam’

subverts borders and proprietary laws and has long been an inherent threat to the colonial apparatus.

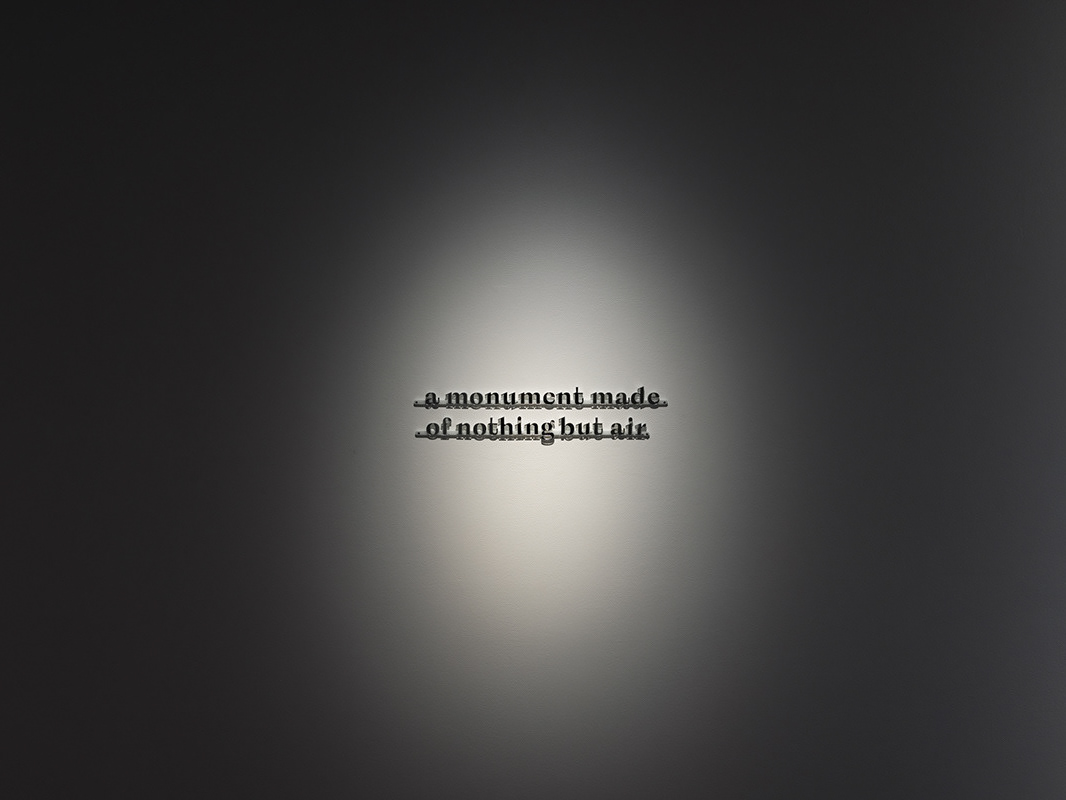

Throughout the gallery stretch a series of fences. putting up walls (wooden fence) is a series of simple, pastoral

wooden stiles, the kind a shepherd might climb to follow grazing sheep. These structures traditionally

perforate a fence’s boundary, creating openings for people to pass through separate pastures. Engraved upon

one stile are the words: a monument to endless space.

Above a brick fireplace hangs a painted facsimile of the very same hearth in gestural brushstrokes. Elsewhere,

another collection of bricks performs a similar act of doubling. Short pillars that resemble remnants of

brick walls are clad in mirrored sheeting. They cast ethereal reflections on the gallery floor. Some are etched

with phrases, the word boundless written in a nostalgic graphic font. A wall or fence typically obstructs

a passerby’s view of whatever lies behind it, a secluded house or hidden garden. In putting up walls (brick

wall), the wall conceals in another, stranger way, showing visitors nothing of what lies behind, reflecting their

surroundings back to them.

Unlike the ‘copy’ of the fireplace or replica fences, other paintings within passing place are not recreations

of existing structures, yet they are laden with allegorical references. The painting on the threshold depicts a

woman lying, supine, with her arms outstretched on an Anatolian carpet. This seemingly fleeting domestic

moment – a lazy summer afternoon perhaps – references a figure posed in Caravaggio’s 1601 painting

Conversion on the Way to Damascus. Another painting, on the borders, presents us with a closely cropped

view of a bouquet of pheasants, their rich, lustrous feathers evocative of a Baroque still life. These restagings

are an act of looking back, acts of visual return that echo the artist’s return to places and locations

entrenched in family memory.

The series of paintings, stopping place, presents monochromatic images overlaid upon backgrounds of

sugar cane plantations, their muted tones lend each painting a photographic sensibility. Sugar cane farming

reached its peak in Queensland in the 1860s, relying substantially on the labour of Indian and Filipino

immigrant workers and the forced labour of South Sea Islanders. These agricultural sites become complex

meeting places for memories of migration and incarceration. A pictorial joke resounds throughout this series.

A traffic light pedestrian sign sits beside the face of Sir Gawain, the Arthurian knight who was notably an

emerald hue. Two green men. You may start walking and pass through here.

Another fence. A ubiquitous, picturesque white picket fence. From its middle, the wooden panels contort

around a yawning inky black chasm, as if a creature from some other nocturnal world was grappling their way

through.

“The experience of being haunted is one of noticing absences in the present, recognizing fissures, gaps

and points of crossover.” In her book Hauntology: The Presence of the Past in Twenty-First Century English

Literature, author Katy Shaw discusses how personal and collective memory can reanimate historical spaces.

The layered and permeable temporality in Passing Place is evoked through the interplay between physical

artefacts and intangible histories. This corresponds with Shaw’s notion of history as a living, contested

presence in contemporary cultural forms. Shaw goes on to say: “the haunted site can function to read the

past and to explain the future through spatial metaphors and representations.” passing place presents us

with a poetic exhibition environment where linear time and space are subverted, distorted and doubled;

concrete forms become porous, riddled with holes and apertures.

In Lewis Caroll’s Through the Looking Glass, Alice climbs into another world through a mirror above her

fireplace. In this new place, upon crossing this lustrous threshold, time unfolds differently, everything is

reversed, and logic unravels. Children’s stories and folk tales frequently discuss the ways in which the world

is mapped and demarcated, and the peculiar occurrences that might happen when such boundaries are

traversed. From Bluebeard’s forbidden door and Hans Christian Andersen’s frozen walls in The Snow Queen,

to the Labyrinth of Crete that encloses the Minotaur, The Secret Garden, hidden away under lock and key

and J.M.Barries’ Pan peeping at the nursery window. These tales remind us that boundaries are not merely

physical but are instilled with the power to transform, challenge, and reimagine the world around us.

passing place maps a range of historical moments and spatial references, collating them in ways that

are spectral and uncanny: an expanded tableaux of copies, maquettes and allegories. Mac’s assembled

structures symbolize the ways boundaries, both geographical and temporal are contested and transformed

within both contemporary and historical narratives. passing place becomes a realm where time and memory

are not fixed, but are open to interpretation, to the possibility of multidirectional movement across both

historical and cultural frontiers. Just as the railway network can reshape a landscape, Mac’s exhibition

invites us to consider how the past continues to shape, and at times disrupt, our understanding of space,

movement, and connection.

Katie Paine is a Naarm-based artist and writer with an interest in science-fiction,

hauntology and semiotics.