Exhibition essay by Emma McLean

Antecedent

Miranda Hine • Jenna Lee • Col Mac

At Nudgee Beach during low tide, there are hard ridges in the sand known as ‘wave ripples.’

These undulations arrive through rolling currents which carve directions where water has flowed,

leaving behind the skeleton of a wave. Their patterns evoke a sense of antecedence. They precede

each-other, tapestry-like and continuous. This natural phenomenon is a visual imprint of time,

yet parallels the way we capture sand in the form of an hourglass to find logic and measurement.

A pattern of its own kind repeats: why must we force order where there is fluidity?

In Antecedent, three Meanjin-connected artists come together in recognition of the threads bind

their work. Together, in their singular styles, they investigate meaning, authorship, presentations

of history, and subjectivity. Considering the past was written with bias, so too are the ways in

which information has been categorised, contained and retold. History is an unreliable narrator.

Taking language as a starting point, Jenna Lee looks to acts of faux-categorisation. She draws

on a text presented as a ‘dictionary’ titled Aboriginal Words and Place Names by A.W. Reed,

still widely in circulation. Reed’s attempt to document First Nations language misinterprets the

enormous variances in language groups across so-called Australia. As Lee explains, ‘there’s no such

thing as “Aboriginal language.” There are hundreds of languages. The text presents words with

no reference to where they came from. It was specifically published by collating compendiums

from the 1920s, 30s and 40s with the purpose to give [non-Indigenous] people pleasant-sounding

Aboriginal words to name children, houses and boats. Yet, the first things taken from us were our

language, children, land and water.’

Lee alchemises the paper of this book to create meaningful forms. Here, she presents a grass

tree which she wove from the book’s pages to recreate this flourishing species that ‘thrives under

elemental forces of deconstruction and reconstruction.’ Working with fire, Lee also presents two

related series. One is an installation titled article-particle (Guyu-Gwa) made up of pigment jars

labelled with the Gulumerridjin word for fire, in which the ashes of Reed’s text are contained.

The other presents pages of Reed’s book on which Lee has scorched Gulumerridjin language.

As she tells, ‘In this context, fire becomes a tool of rejuvenation and rebirth, breathing new life

into the previously dislocated words.’ Lee’s engagement with materiality always intersects with

ancestry. A Gulumerridjin (Larrakia), Wardaman and Karra-Jarri Saltwater woman with mixed

Japanese, Chinese, Filipino and Anglo-Australian heritage, Lee reflects her identity across

disciplines with exquisite skill.

Meaning attributed to the Australian landscape has often evolved from European mythology and

culture; its characterisation mostly tied to experiences of the uncanny, of mystery, disappearance

and dread. Think of the unfortunate tale in Waltzing Matilda, or the melancholy film Picnic at

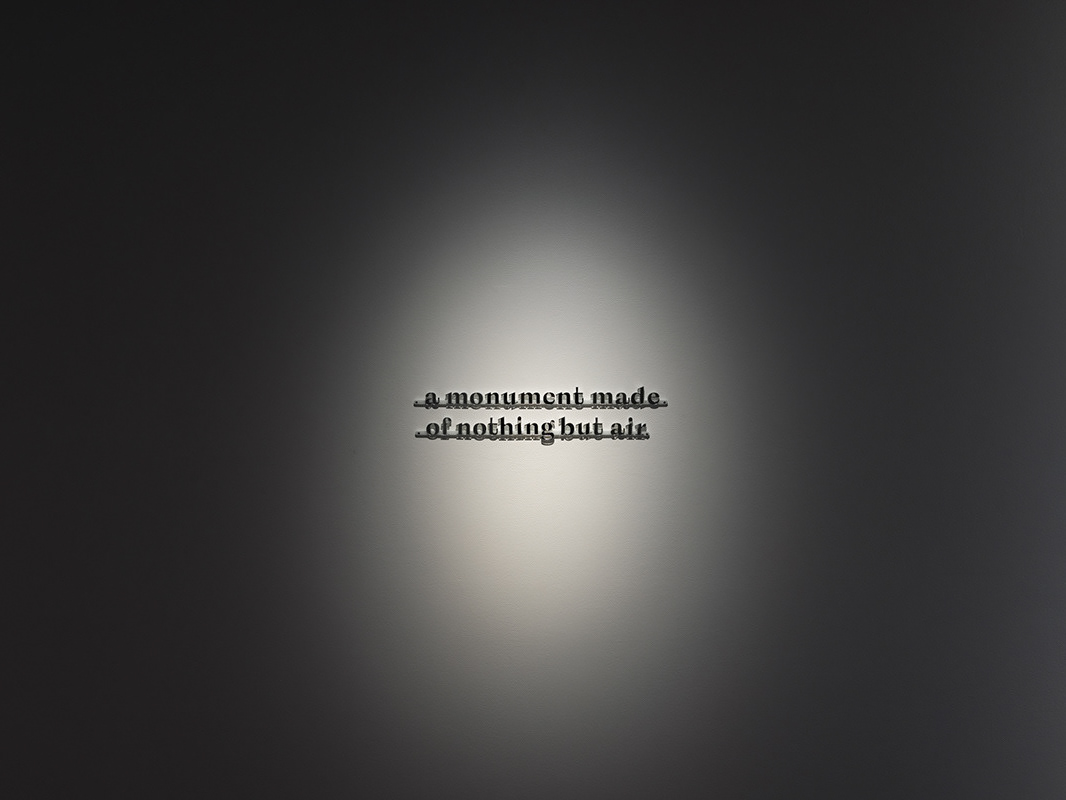

Hanging Rock. In his installation somewhere inside the vanishing point, Col Mac challenges these

miscastings. Here, Mac queries the European technique of the ‘vanishing point’, where parallel

lines intersect to mark the location of the horizon. While applied in many colonial paintings,

the vanishing point misjudged the Australian bush in all its density, scrub and abundance.

In his suspended artwork, Mac depicts the icon of a ghost as a motif for the bush’s supernatural

characterisation. The artwork’s mirrored surface shatters light within the gallery space and, by

creating a sensory experience of the dappled light which filters through leaves, Mac draws us

into the landscape and through the trees. Inviting us closer, Mac’s paintings focus on several

detailed views of two trees he encountered in the bush. He observed that the trees had grown

so closely together that their branches were entwined. Revealing this limited view, we focus

on the branches that delineate the paintings and create shapes for light to shine through, like

stained glass windows throwing shadows on the forest floor. In shifting representations of the

bush towards that of physical experience, Mac ensures his depictions reflect an environment

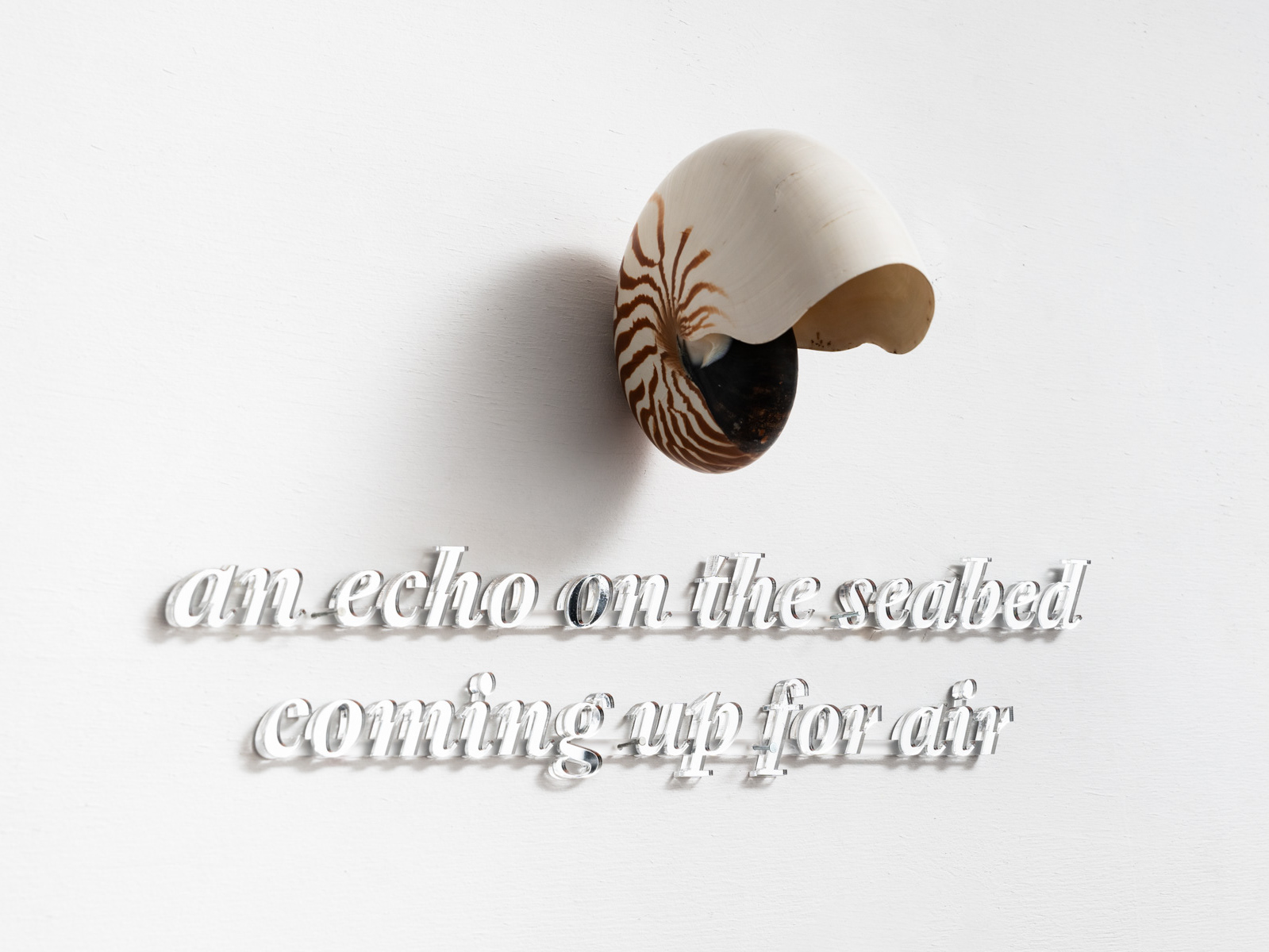

that is growing and interactive. Mac is an artist of remarkable range. From design to painting,

sculpture, installation and text-based practice, he continues to disarm with each approach.

Departing from the natural world, the buildings we imbue with academic authority such as

galleries, museums and libraries also reveal surprising approaches to the past. In her work

as an artist and curator, Miranda Hine agitates methods of presentation to ask whose history

institutions present, why and how. Currently based in London, Hine presents ten new paintings

which are the result of site visits to historic houses in the UK during late 2023. Many of these

houses were the homes of figures celebrated by history, such as John Keats, Charles Dickens

and Sigmund Freud. With gentle humour, Hine focuses on idiosyncratic methods of presentation

within these public homes. In some cases, chairs were cordoned off or restricted by signage. In

others, they were available to be used (you can lay on the couch in John Keats’ house) and in one

venue, a pine cone was strategically placed on the chair’s seat.

Rules around the presentation of objects and artefacts are myriad. While often guided by

financial value, there is another type of value-judgement that comes into play of a discretionary

nature. In the case of these chairs, we see that degrees of interactivity are fluid and can depend

on contrasting levels of trust. This series marks the first in which Hine directly integrates

methods of curatorship within her paintings. While presenting in the still life genre, these

artworks go further by offering windows into scenes which have been staged from an archival

perspective. They are both impressions and documentations. With characteristic brushstrokes

that weft, weave and build joyful ambiguity, Hine’s skill of capturing the particular tone and

palette of a location is intuitively felt and, in the mind of the viewer, re-invented.

In Antecedent, three artists and collaborators meet to harness shared queries about

authorship, colonial legacies and logic. As we reckon with the past, their artworks splinter the

ways we understand what has come before, and how we communicate today. They show us

that chronology is used as a tool for controlling the archive, but whose archive? And whose

chronology? These questions are as shifting sands, changing with time and its many lessons.